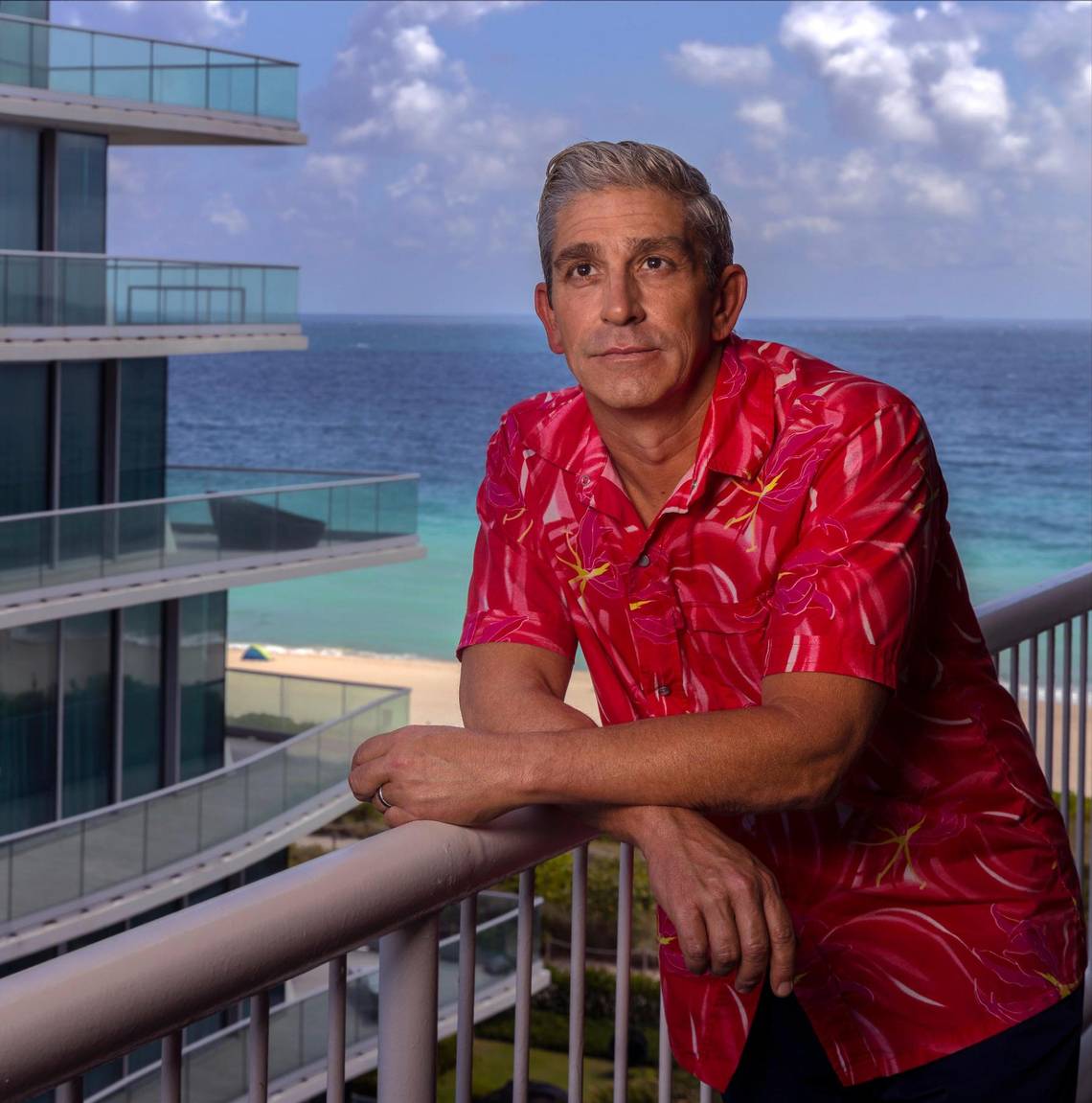

Richard Blanco joined us for an early morning Zoom interview, from his Miami apartment, for a thoughtful talk about big questions and small observations, and the anticipation he is feeling to return to Maine Media in person, this summer. His husky baritone, an octave lower than when he reads his poems aloud, was still dusted with morning voice.

When he talks about how a poem is made memorable by “being built out of a strong emotional center and having a soul where you understand the very marrow of the poet’s feelings or the prose and what they have at stake” one realizes they are not only in the presence of a fine poet in his own right, but of a rare artist who can show others how to delve other dimensions and emerge bearing just the right words, clamoring to marry numinous human emotions.

As Maine Media returns with a full lineup of on-campus workshops this summer and fall, we’re looking forward to hosting Blanco for his workshop, Poetic Urges. This weeklong workshop promises to be an exciting opportunity for students to dive into the world of writing poetry, with Richard Blanco as their guide.

“I don’t consider a poem really done until it is shared, until I see that poem in somebody’s eyes and somebody’s smiles and somebody’s tears. Until they share their stories with me about what the poem did for them or what the poem reminded them of in their own lives. It completes the cycle. And when we do that in places like Maine Media, especially during the weeklong poetry intensive workshops, that’s really something special,” he noted.

Poetic Urges will provide a community for conversation, supporting students as they immerse themselves in the study of poetry as a craft, as well as using free writes and prompts to develop their own poems.

Two-Year Hiatus

This summer will mark two years since Blanco taught his workshops in person at Maine Media. During the pandemic his classes were taught online. He is eager to return to the Midcoast to teach, not too far from his summer home in Maine, where he quarantined with his husband in the early days of Covid.

It was a year of cooking together, catching up on their lives, taking a deep dive into each other and even dying their hair bright colors because they were so bored. “Oddly enough, I have the fondest memories of those months,” he recalled.

Quarantine also demonstrated to him “how essential every single one of us is to our society” including the cashier who shows up to work every day and the Amazon delivery person, who showed him “what an interconnected world we are and how fragile it is.” He wound up penning a poem about those realizations for The Atlantic.

Another thing that happened was he began “noticing really small things” like watching his cut finger heal over a few weeks time that led to writing about the body. “I focused on what was immediately in front of me, which, ultimately, is what artists are supposed to do.”

He is currently putting together a new book comprised of many poems that were written during the pandemic, which has surprised him with its consideration of big questions of mortality and the external cycles of life. “Watching the fall leaves like I had never seen them before,” he said.

“I don’t consider a poem really done until it is shared.”

He made note of a micro-to-macro paradox that played out for him, as he experienced how small things spoke to bigger truths that emerged.

“We kind of all have a post traumatic stress right now. A knowing that this could happen again, in another context, in another way. Like with the war in The Ukraine, we’re understanding this could be something bigger that could pause the world again. I’ve had fears of nuclear holocaust since I was in the third grade during the height of the Cold War,” said the poet, who was educated as a civil engineer.

The past years have impacted the world collective, he noted. “Catastrophes do change us. I mean, whether we want to acknowledge that or not, it still looms large over everyone.”

Teaching Poetry on Campus

At Maine Media’s campus this July, Blanco will lead a group of up to 12 students on a weeklong exploration into poetry called Poetic Urges. It will be an opportunity to learn the important basics of poetry for those who yearn to be part of a community in conversation with others on craft.

“I really like being a workshop leader for novice writers. I love the experience of seeing their minds explode, witnessing that shift in their sense of poetry in just five days. It’s a gift for me to be able to give them that gift. To give them that step ladder, so to speak, and then to let them go onto the next step in their journey as writers with hopefully not just more skills but more confidence,” he noted.

Blanco is also known for incorporating photographs, as ekphrastic platforms, in his workshops. He got the idea when he first began teaching years ago at Maine Media, which has been primarily known for its photographic education, and wanted to pay homage to what happens on its campus. He wanted to foster cross-pollination, using images to inspire words, and connect to the school’s rich history.

This overlaps with what photographs have meant over the course of his own life and refers to his mother’s staunch efforts to keep fierce records of her entire side of the family, whom she left behind when her family exiled from Cuba and went to Spain, where Blanco was born two months later. After just 45 days, his family immigrated to Miami, where he was raised and spent the bulk of his years.

“Those photographs became portals to understanding this other world, that was supposedly very much mine, that I had never seen or experienced firsthand,” Blanco noted. “I think photographs are ingrained with stories and narrative. They evoke things, much like a poem does. Every time I see a photograph, I want to climb into it and pull a poem out of it.”

John Paul Caponigro, digital photographer and fellow Maine Media instructor, was among Blanco’s online poetry students during Covid, one of several artists who cross-pollinated into various creative genres at the school.

He said he had met Blanco briefly and knew of him but didn’t get to know him until he studied with him. As a teacher, he characterized him as “super.”

“Richard’s this big-hearted, very warm individual. He’s got a great grounding and very unique experience – Cuban immigrant, first-Latinx inaugural poet, living in Maine, teaching in Florida. Very interesting perspectives. He’s got this great laugh, great smile, wit and humor. It helped foster the warmth and community in the workshop. I think in a way, Richard was the main hearth, or home fire, that started this other poetry community that we continue,” said Caponigro.

Blanco As Poet

One of Blanco’s strengths as a writer is his presentation when reading his own poems, a skill he also helps cultivate in his students. He thinks of his public readings like concerts, which when lifted off the page, develop cadences, pauses and inflections.

“Poetry arose out of song and chant and prayer. For thousands of years before it was put on the page, it was shared around the proverbial campfire. The telling of stories and folklore were meant to pass on and preserve knowledge. So, when we come together as a community of writers, that energy starts to surface and actually helps serve the writing,” Blanco said.

“Our spoken voices are musical instruments that bring about change in the poems. They are built from a strong emotional center and there are many elements that make for a memorable poem. For me, it’s got to have a soul, where you understand the very marrow of a poet’s feelings, what they have at stake. It makes us realize our experience as a human being and it imprints on us. It paves the way for transformation and transubstantiation that involves our entire body and being.”

“Every time I see a photo, I want to climb into it and pull a poem out of it.”

In his own artistic practice, Blanco has recently returned to having artist dates with himself (a term Julia Cameron coined in her iconic The Artist’s Way book series) when he goes off into the world to notice things of interest, to just have fun and accept whatever happens.

“I can’t just say I’m going to think about poetry; it has to come from a kind of surrender and tranquility. If you’re looking for poetry, you’re not going to find it, let’s put it that way. Then it becomes a task instead of something that emerges naturally,” he noted.

As he gathers poems for a new book, Blanco circles back to that idea. “I arrange the poems in a way that tell a story. If you read a whimsical poem, then you want to follow with a more dramatic piece. If you read a ballad, you want to follow with something shorter, lighter. There’s an ebb and flow to how the poems fit together.”

Impacting & Understanding Cultural Changes

In 2013, Blanco, now 54, broke a lot of ground when he was tapped by the Obama administration to write and read his One Today poem at the first inauguration. He was the fifth person to serve as inaugural poet, the first immigrant, first Latino, first openly gay man and, at the time, the youngest poet to serve in the role.

As both an undergraduate and graduate-level professor, he sees students having polarized reactions in terms of social justice and a sense of a call to action in the world. In the younger people, he sees the perspective that “I do have agency in this world. I need to exercise that and like, totally go for it.”

In the older demographic, he feels a kind of retreating. “A sort of dormancy, where they feel like the world is bigger than them and they can’t imagine they have agency. I try to help them all understand they do have agency. The agency doesn’t have to be something huge, but to start with owning their own lives and experiences, and to realize those experiences matter to other people. Because in art, of course, what we’re doing is taking the time to explore and investigate our own experiences, so that others can relate, make discoveries, or have their own growth experiences,” he explained.

In his Latinx history course, Blanco has his students read a lot, both history and literature, and ground themselves in that.

“While this pandemic has been incredibly impacting, 1968 wasn’t a great year. Colonialism wasn’t such a great period in human history, nor slavery. To help them understand that history has long arcs and while this time may seem completely suffocating, the reality is, history goes through its movements and loops. Hopefully, things come out better on the other end. We have to keep those lessons, if not consciously, in our subconscious mind,” he noted.

“I have to do that for myself in regard to how I relate to our times, whenever I feel ‘Oh my God, it’s the end of the world’ that maybe it is the best of times and the worst of times. It feels like both,” said Blanco.

Learn more about Richard Blanco at www.mainemedia.edu/writing